The Secretary Problem

The secretary problem is a classic decision-making model about when to commit under uncertainty. It captures a common situation: you must choose the best option from a sequence, you see options one at a time, and once you pass on an option you cannot return to it.

The Setup

- You will evaluate N candidates, arriving in a random order.

- You can observe and rank candidates only relative to those you have already seen, not against the entire pool.

- After rejecting a candidate, you cannot go back.

- Your goal is to select the single best candidate overall.

The Optimal Strategy

Surprisingly, there is a mathematically optimal strategy:

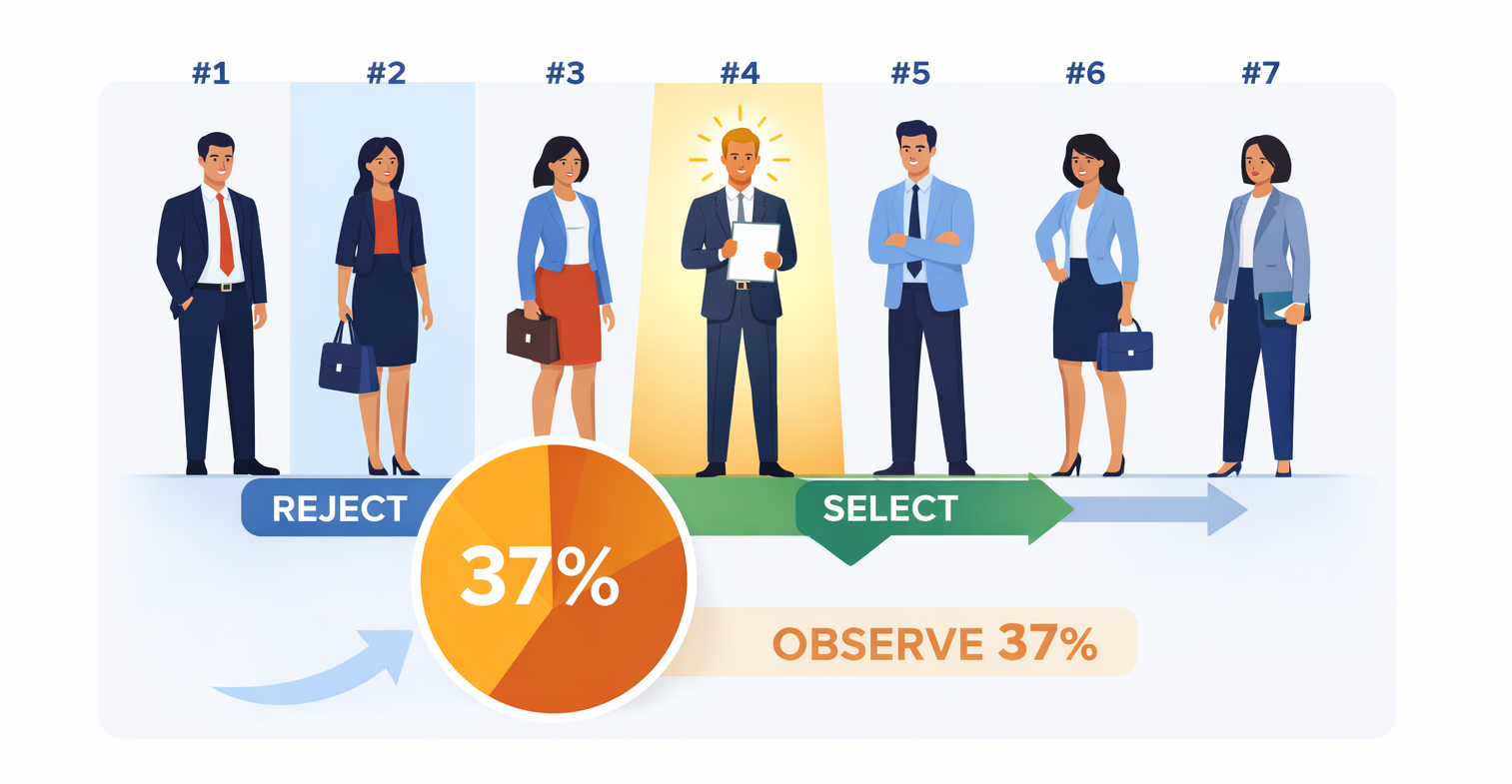

-

Observation phase

Reject the first ~37% (1/e) of candidates outright.

During this phase, you are not allowed to select anyone — you are only learning what “good” looks like. -

Selection phase

After the observation phase, select the first candidate who is better than all candidates seen so far.

This strategy maximises the probability of choosing the best overall candidate.

Why 37%?

The number comes from mathematical analysis of optimal stopping theory.

- If you observe too few candidates, you lack a meaningful benchmark.

- If you observe too many, you risk passing the best one.

- The balance point that maximises success probability converges to 1/e ≈ 37% as N grows large.

With this strategy, your chance of success is also ~37%, which is the theoretical maximum under the problem’s constraints.

What the Problem Is Really About

The secretary problem is not about hiring per se. It models:

- Sequential decisions under uncertainty

- Irreversible choices

- Limited information

- The trade-off between learning and committing

In essence, it answers the question:

How long should you explore before you exploit?

Key Assumptions (and Their Importance)

The result only holds if:

- Candidates arrive in random order

- You care only about selecting the single best option

- Decisions are irreversible

- There is no cost to rejecting candidates (other than opportunity cost)

Changing any of these assumptions changes the optimal strategy.

Practical Takeaways

- Early decisions should prioritise information gathering, not optimisation.

- A deliberate “no-commitment” phase can be rational, not indecisive.

- Once sufficient signal exists, delay becomes more costly than action.

- Perfect information is unnecessary — structured heuristics can be optimal.

References

Share on X (Twitter) Share on LinkedIn Share on Facebook